In December 2022, Life Support set sail on its first mission.

The report “Saving Lives in the Abandoned Sea: One Year of Life Support” tells the story of the first year of our ship’s search and rescue missions: the outcomes, the difficulties and obstacles encountered by the shipwrecked people and our team in the central Mediterranean, the political and humanitarian context, and the approach to migration across Italy and Europe.

Through survivors’ testimonies and moments from our own search and rescue (SAR) operations, we show what it means to save lives at sea and why it is an overriding duty. An obligation enshrined in international maritime law and multiple SAR Conventions, but one that is not on the European political agenda.

Progressive institutional disengagement following the conclusion of the Italian government-led search and rescue operation Mare Nostrum in 2014 has clashed with the urgency of guaranteeing assistance to those in distress on the deadly crossing of the central Mediterranean.

Data from Our First Year at Sea

“Saving Lives in the Abandoned Sea” retraces missions and rescue operations conducted in international waters throughout our first year at sea, which led to the rescue of 1,219 people.

From the survivors’ countries of origin to the medical activities on board, from alerts of distress cases to the testimonies collected by our cultural mediators, the report documents life on board from the point of view of the medical and non-medical staff, the crew and the rescued people.

Within a shrinking humanitarian space, due to the continued criminalisation of NGOs operating at sea, the report also bears witness to the consequences of a European migration strategy based on the externalisation of borders: ongoing human rights violations in third countries like Libya and Tunisia and the effects of established and new bad practices at the national level which restrict NGO search and rescue activities, like Italy’s Piantedosi Decree.

The people we rescue at sea are not used to being cared for by anyone. For months, sometimes for years, no one has taken care of them. About half the people we see have conditions, often trauma, dating back months before the rescue. By the time we see them in the clinic, after months of neglect, their conditions are often chronic. This is also true of the patients’ psychological condition. In this first year of activity, we have not had any serious clinical cases or cases that would require immediate evacuation. So, we find ourselves writing to the health authorities the generic formula “general condition: good/satisfactory,” which might be clinically true, but is actually grossly inaccurate. No one would say that, after what they have been through, they are well.”

Roberto Maccaroni, Medical Director Life Support

The Piantedosi Decree and Distant Ports

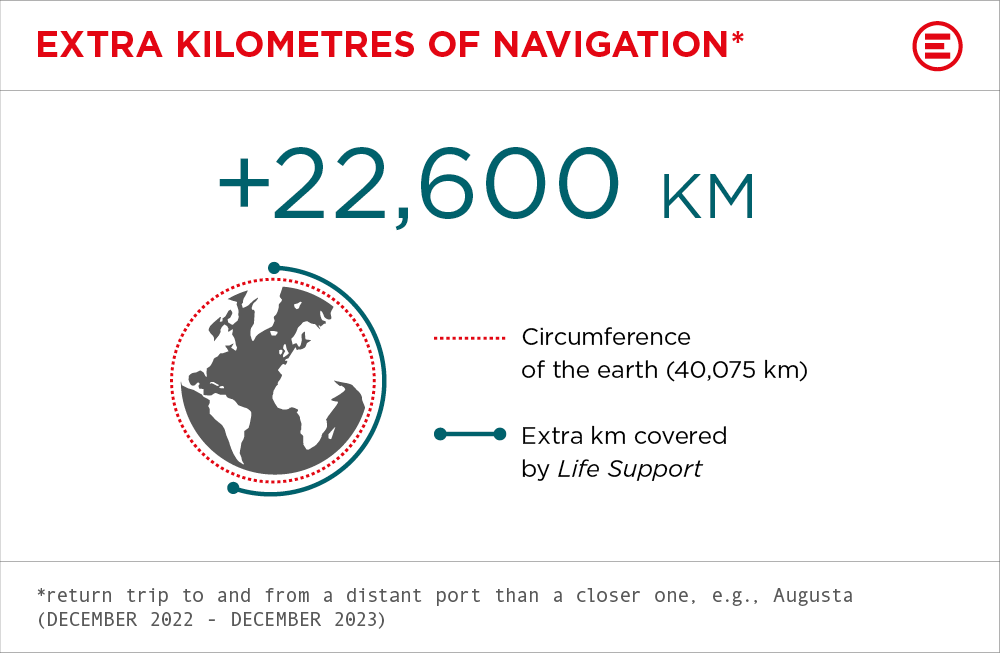

Alongside the measures of Italy’s Piantedosi Decree, which contains provisions that effectively prevent multiple rescues by NGOs, is the systematic practice of assigning NGO ships to ports far away from the areas where rescue operations are carried out.

In one year, we have carried out 24 rescue operations in the central Mediterranean, the most dangerous migration route in the world, covering almost 40,000 km over a total of 105 days.

To reach distant ports assigned by the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre, Life Support travelled an average of 630 nautical miles, taking 3.5 sailing days per mission. Navigating to distant ports and back to the Mediterranean required an extra 56 days of sailing when to compared to a port in southern Italy, removing the ship from SAR regions and diverting valuable time from search and rescue activities.

For these unnecessary sailing days, EMERGENCY incurred an expense of 938,248 euro.

LIFE SUPPORT’S FIRST YEAR AT SEA

A Snapshot of Migration by Sea in 2023

Every year, thousands of people undertake the perilous Mediterranean crossing to escape wars, persecution, human rights violations, poverty and the effects of climate change, in search of protection or better living conditions. To reach European shores, they board collapsing, overcrowded boats organised by human traffickers.

According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), 2023 was the deadliest year in a decade: 8,565 people lost their lives along migration routes around the world. This is the highest figure recorded since the deaths and disappearances of migrants on these routes began to be systematically tracked in 2014.

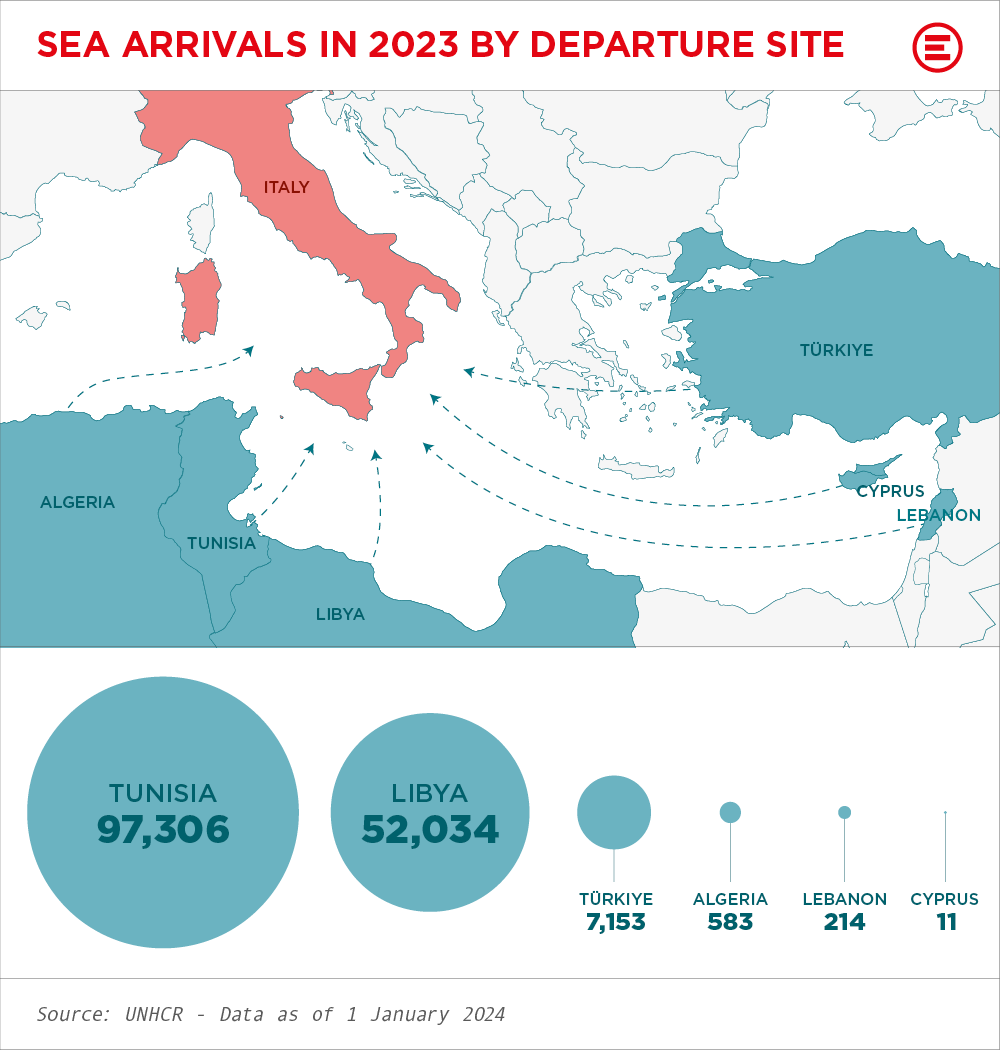

In 2023, there were 2,734 ‘missing migrants’ in the central Mediterranean, an average of more than seven people disappearing every day.

Italy is the top country for arrivals, receiving 157,301 people. About 12% were unaccompanied minors.

Due to its magnitude, this humanitarian crisis must be tackled by overcoming political instrumentalisation and with the joint support of civil society and formal institutions. However, what currently prevails is a securitarian and hostile attitude toward migration: the assignment of distant ports of disembarkation, the prohibition of multiple rescues, failures to rescue, agreements and protocols outsourcing containment to third countries, interceptions and push-backs are just a few of the choices made by governments which treat migration as a security problem and not as a structural issue of our time.

In response to this humanitarian crisis, we have chosen to play our part directly, in a project that saves lives at sea and reaffirms the need for a humanitarian approach.

We believe that rescuing people whose lives are in danger at sea is a duty, equal to our commitment to saving lives and providing care to the victims of war and poverty in our hospitals around the world for the last 30 years.