In all of EMERGENCY's facilities around the world, we invest in women’s professional development -…

Providing Long-Term Care to People with Disabilities in Iraqi Kurdistan

Background

Iraq is among the most heavily mined countries in the world: according to the Landmine Monitor 2022, over 1,200 km² of the territory is littered with landmines and over 500 km² more with improvised explosive devices (IEDs). In 2021, the United Nations Mine Action Service extracted 9,000 unexploded ordnances from the ground. Yet according to the latest estimates, 20 million mines and between 2 and 6 million other explosive remnants of war remain.

During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s and the subsequent Gulf War in 1991, millions of mines were planted on the ground, especially in mountainous areas. The aim was to extend the conflicts and hinder recovery; even decades later, this explosive legacy continues to injure and kill.

Since 1996, the reality of the patients treated at the Surgical Centres in Sulaymaniyah and Erbil – both of which have now been handed over to local authorities – confronted us with the need to provide care even after wounds have healed: to ensure that people with physical disabilities have continuous assistance, for their entire lives.

With this mission, in 1998 we opened the Sulaymaniyah Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration Centre. Producing prostheses, reintegrating patients within society, and accompanying them towards economic independence are fundamental services for the men, women and children who have lost limbs because of landmines or have other disabilities.

Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation: The Heart of Our Work

Spread over one floor, the 2,500-square-metre building has no architectural barriers between its many rooms: the orthopaedic workshop, the training room, the canteen, the guest house for patients arriving from outside Sulaymaniyah.

Since the project began, we have produced around 12,600 prostheses for upper and lower limbs, built with thermoformable materials and to ensure flexibility.

After the prosthesis has been fitted, the patient begins the rehabilitation process in the training room: a gym equipped with parallel bars, planks and platforms for gradually more complex exercises. More than 63,000 physiotherapy sessions have happened here.

The Other Half of the Cure

Helping our patients for the long-term is ‘the other half of the cure,’ encompassing complementary axes of care:

The professional training of former patients and their employment by EMERGENCY: the Centre has been managed for more than 15 years by only local staff, 65 Kurdish colleagues who work daily to ensure its total functioning.

Psycho-social support through the Income Generation Programme, which helps people with significant disabilities start a family business and has the dual function of providing a source of income and easing them back into society.

The home modification programme, an intervention to remove architectural barriers in patients’ homes.

A prosthesis is not just a health device: it is the way we help parents get back to picking up their children, or children to walk to school… It’s getting back to having hope in the future. To go back to holding a pair of scissors, a drill, combines hope with the dignity of being able to work again and generate an income to support your family.”

– Faris Hama, Director in Sulaymaniyah

Jabar, patient

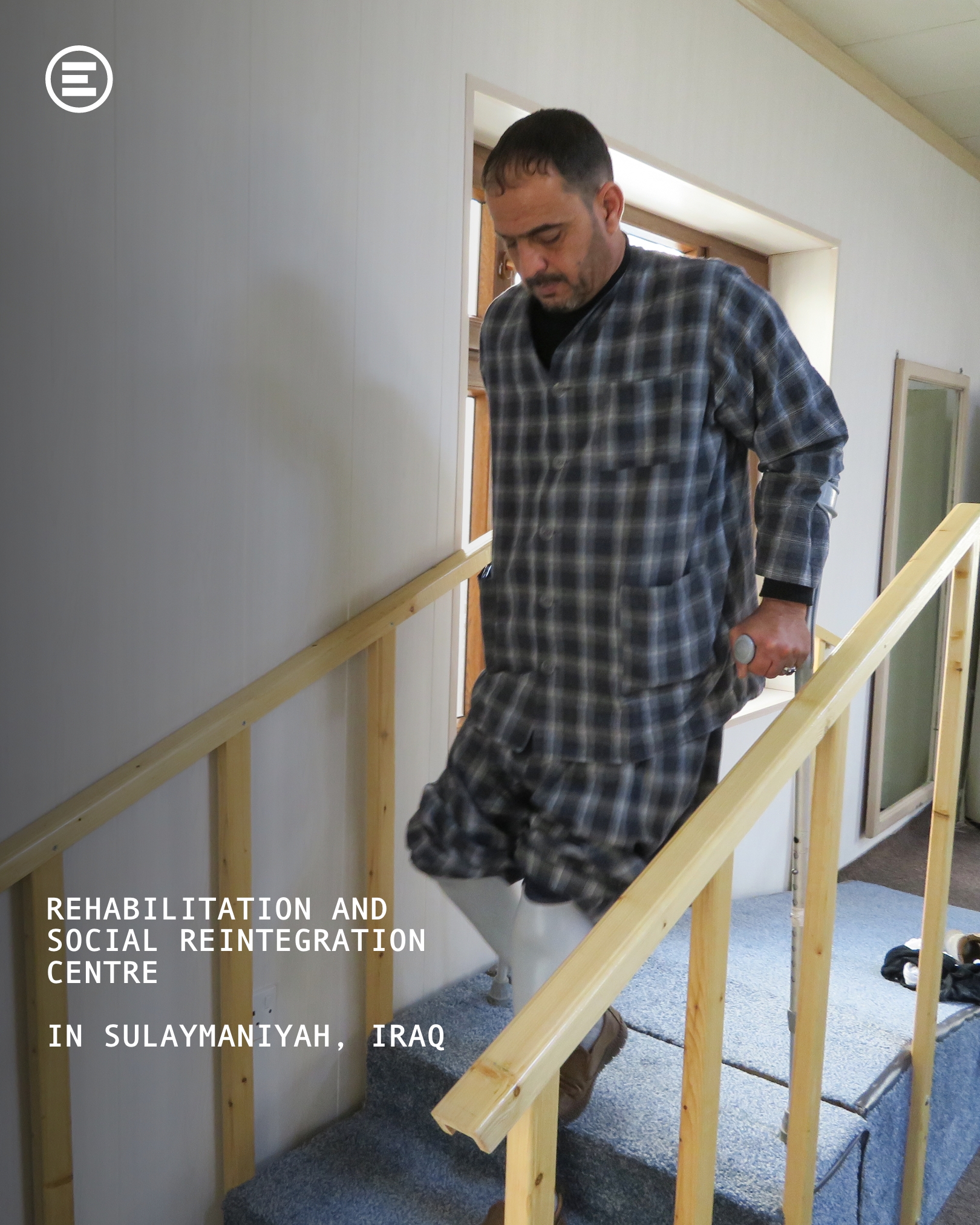

So many patients have travelled up and down these steps over the years, becoming familiar with their prostheses. Jabar is one of them.

So many patients have travelled up and down these steps over the years, becoming familiar with their prostheses. Jabar is one of them.

In November 2004, he was on his way home from selling his crops in Kirkuk when a car close to him suddenly exploded. That tragic moment caused him to lose both legs. Jabar first came to our Rehabilitation Centre three months after the amputation. Here, we built Jabar proper prostheses, and he continues to return for periodical follow-ups and adjustments.

Jabar is a father to 8 children, 6 of whom still live with him and his wife. He admitted that it is difficult to continue farming and sustain such a large family. Nonetheless, his perseverance goes hand in hand with our dedication to support him with exercises, physiotherapy, and optimisation of his prostheses.

As Shady, one of the physios here tells us: “We want to support disabled people in the community so that they can continue living how they want to live.”

And that’s where EMERGENCY’s care goes beyond just medical treatment. It is about human bonds and opportunities. We’ve been creating them here in Sulaymaniyah for 25 years.

Sargul, patient and EMERGENCY colleague

“For myself as a disabled person, EMERGENCY is the house of hope and happiness.”

“For myself as a disabled person, EMERGENCY is the house of hope and happiness.”

At just 2 years old, Sargul contracted polio, which affected the use of her right leg. She enjoyed school but struggled to watch the other children running and playing, which made it difficult for her to attend. “Then,” she says, “life continued.”

Sargul was working as an accountant when she learned that EMERGENCY was opening a new Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration Centre in Sulaymaniyah. She came for an interview and we soon hired her as an Ortho Officer. She also received her own orthosis, which is regularly adjusted for her needs. She tells us, “I am very happy for my employment. Since the first day, I started to help disabled people by supporting them psychologically.”

Thanks to colleagues like Sargul, our Sulaymaniyah hospital has been a place of hope and new beginnings for over 12,000 patients since 1998.

Sangar, patient

This little patient between Burhan, physiotherapist, and Shamal, Ortho Technician, is Sangar.

This little patient between Burhan, physiotherapist, and Shamal, Ortho Technician, is Sangar.

Sangar is just 10 years old. He lost his right arm and right leg in an accident. He was on the roof of his house, at first to help his aunt wash it and then play by himself. While looking down at the yard below, he started feeling dizzy, lost his balance and grabbed a high voltage cable to avoid falling down. He received an electric shock. In just one year, Sangar went through two months of hospital admission and 18 surgeries.

But, this picture speaks for itself. His prostheses have allowed Sangar to take back his future. When children introduce themselves, they mention two things which mean the world to them—school and football—and Sangar is no different. He has returned to school, and we’re determined to help him continue playing football with his friends as he did before.